How To Succeed At Everything

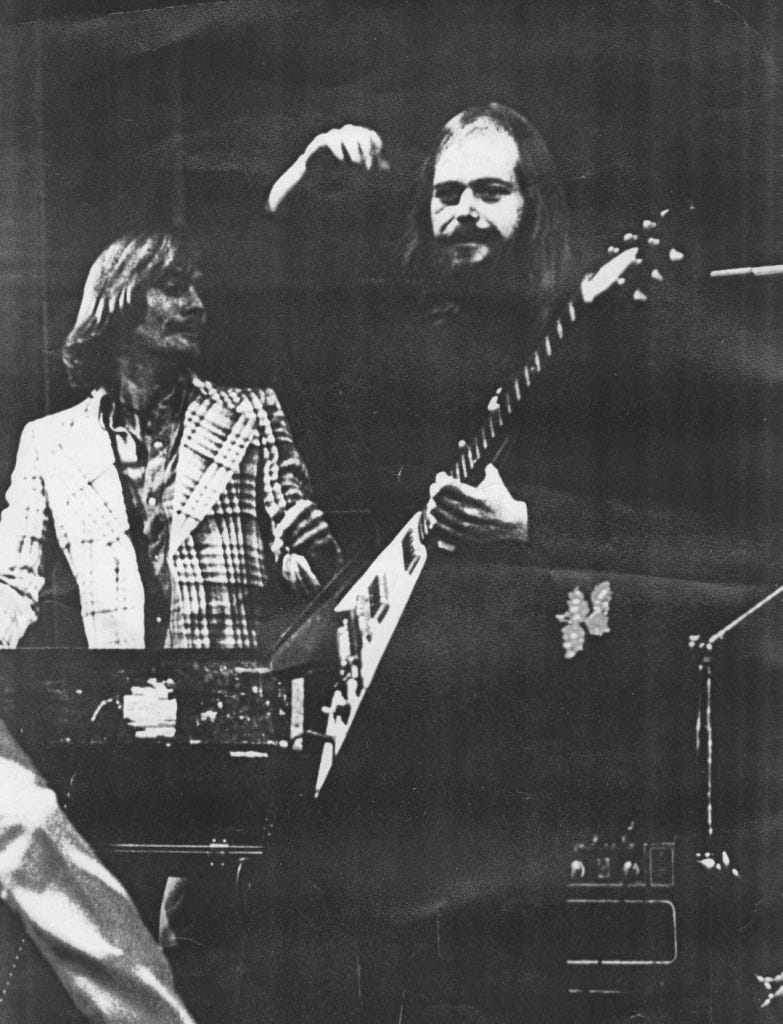

Guitarist Ray Russell talks about his life as a studio ace, as well as his parallel career as a brain-crushing experimental guitarist

Ray Russell lives a double life. Way back in the 1960s, he landed a gig—while still in his teens—with noted film composer, John Barry, as the guitarist in Barry’s touring ensemble, the John Barry 7. That led to studio work, where Russell was a first-call player. He did that for decades, and played on thousands of sessions, which include everything from jingles, Top 40 hits, and full length albums, to documentaries, films, and popular television shows. As the years wore on, he began scoring for film and TV as well.

However, parallel to that respectful, if awesome, career, is Russell’s work on the fringes as a trailblazing jazz artist. He released his first album in the late 1960s, which was somewhat straight-ahead, if edgy, guitar-centric jazz. But by his third release, 1973’s Secret Asylum, that had evolved into bombastic, head-splitting, limit-pushing madness. He’s continued down that path—while never taking a break from mainstream session work—and that led to his lengthy association with jazz legend, Gil Evans, and continues with his recent releases on Cuneiform Records.

Although, as far as Russell’s concerned, music is music. “Free jazz was really interesting to me as it was coming up,” he says in our interview below. “But the thing is, to me, it’s all music. It’s groove and it’s free. Obviously, the free jazz thing is a lot more group creativity and it’s far more dynamic to actually get that going. Less clues in a way.”

Half a century on, Russell shows no signs of slowing down, and Corona be damned. I spoke with him from his home in Brighton, in southern England, and we talked about his years in the trenches as an A-list studio guitarist, sessions with iconic artists like Marvin Gaye and Tina Turner, his experiences with Gil Evans, his parallel career as an improvising guitarist, writing for film and TV, and his recent collaboration with noted experimental guitarist, Henry Kaiser.

How did you land the gig with the John Barry 7?

I was at school, and then I took a job at 16 in a kind of music warehouse. It was very strange. I was moving cartons from one side of the warehouse to the other, because they didn’t have a proper lift. I used to practice guitar in the loo—in the restrooms—at lunch time. There was a paper out then called the Melody Maker, which is long since gone, and they listed jobs, or “Situations Vacant.” I read an article that John Barry was looking for a guitar player, because the original guy, Vic Flick, had left. I called the number, and the tenor player in the band, Bob Downes, answered the phone. He asked, “Do you know all the tunes?” I said, “Yes.” I didn’t. He said, “Why don’t you come down?” About a week later, I took the bus to this place that used to be an old cinema. Most of the band were there, and they started putting the parts up, like for the “James Bond Theme.” What they didn’t know was that my parents were really good to me. They bought me a little record player and also John Barry’s Greatest Hits. I put the vinyl on and woodshedded for the week [before I went down to meet the band]. At the audition, I went along, the parts were in front of me, and luckily they were the songs I had learned. I played it through, and they said, “Wow, this guy is great, and he’s so young.” John wasn’t there, so they phoned him up and said, “This guy is good, he can do it.” Two days later I was on the road. But then came the crunch moment, about two or three weeks in they had a new tune, which we looked at, and the bass player looked over to me and said, “You can’t read, can you?” I said, “No.” He said, “Don’t worry, I’ll teach you how to read.” So that was it. That’s how I bluffed my way into the music business.

Guitar players are notoriously poor readers, but were you able to get to a level where you could read pretty much anything?

Yeah. What happened was, in the van going to gigs, I would get music, and the bass player [Ray Styles] would say, “Play that.” I had a little acoustic—you can imagine, we were all grouped together quite tightly, and I’d have to get this acoustic out to play, it was very funny—but he taught me to read. I got more confident, and by the time I left I was probably quite a good reader, which is just as well.

Is that what led to studio work?

I left John because the gigs were getting less. I did one of the James Bond films for him, From Russia with Love, which was great. It was quite a lot of money to pay the band even then, we were eight or nine people, so that stopped. That’s when I joined Georgie Fame. How I did that was, I was at a session—I had been doing a few of them, and it was one of the first ones, which was pretty dismal—but it was at a very well-known studio called Lansdowne, which doesn’t exist now. There were three guitar players on the session. It was me, John McLaughlin, and Jimmy Page. The three of us. We were having a conversation, and I said to Jimmy, “What are you doing?” He said, “I am going to stop doing sessions and I am going to form a band.” John McLaughlin said, “I am leaving for New York and I am going to join Miles Davis.” I said, “I wonder what I am going to do?” John McLaughlin said, “What you’re going to do is carry on doing this, and you’re going to join Georgie Fame, because I am leaving.” I started doing more sessions, and I did join Georgie, and had a great time.

What was the studio scene like? Could you do anything from jingles to albums?

Yeah, and in the U.K., you just did anything. I think in the States people got more known for what they were doing, and had those types of sessions where they played a similar style. We just did anything. We never knew.

You found out when you showed up?

Yes, but that changed though. As time went past, people like me—I suppose what was then the new school—started to ask questions, like, “Who’s it for?” That was a bit of a no-no. But we started asking questions, because we wanted to know what to bring. We dared to get artistic about it. When rock started, it became very different, and we became involved. We weren’t just hired hands to walk in and play. One of the first sessions I did, there was another guitar player there. He was old school—I don’t mean to be rude about it, he was a really great player—but he looked down, and I had a couple of effects pedals. He said, “Have you got your gimmicks with you?” None of that music was real to them, so emotionally they weren’t into it. That’s how that started, because we were. It was the music we liked.

Did you have an assortment of guitars that you would bring to sessions?

In the late-1960s, 70s, and early-‘80s, there were so many sessions that you could work day and night seven days a week. There were three teams called the A, B, and C team. The A team was first call and so on. Without sounding pretentious, I was on the A team and between us, we all chipped in and hired a roadie to work for us full time. We all had two sets of gear. It was so busy. Our roadie would drop one off and then he’d drop the other one off. Everything was duplicated, apart from if you needed a special guitar, which you’d take with you. But we had three guitars duplicated—tools of the trade, like a Strat and a very good acoustic—pedalboards were duplicated, and amps. He’d set it up, and then we would be able to walk in. Sometimes it was so hard in between sessions to get to the place, but it was already set and nicely humming. We could walk in and play, which is very big time, but that was just the way it was. There were times where I would finish a session in the morning and the producer would say, “Can you come back and do some overdubs later?” By 10 o’clock that evening I’d go back and start doing overdubs while they were in the middle of mixing it. I’d not finish until about two in the morning.

Would artists you recorded with take you on the road as well?

Sometimes. A few people. People would do a tours to promote their records, but the trouble with that was that you couldn’t be away too long from the studio scene. It was like you were holding people back like a queue at a concert to get into that scene. You had to make sure you weren’t away too long, or they’d go, “Ray who?”

Were American artists coming over as well? I heard a story that you played with Marvin Gaye, and others like that.

Marvin Gaye, he was obviously great. He phoned up the music contractor—or the fixer as we called her—and he said to her, “I am coming over to England. Give me the best of your session people, because I want to see what they’re like.” I used to virtually live at AIR Studios on Oxford Circus, which is George Martin’s place. That’s where everything was done. Marvin came with his minders. He went straight into the control room and he sat there. Somebody came out, the musical director, gave us the stuff, and said, “Just get into it.” We asked, “Any instructions?” He said, “No, just play and see what happens.” We started about 10 or 10:30 in the morning—by the time we got sound—didn’t break for lunch. About five o’clock—and Marvin hasn’t said a word—the musical director said, “Marvin would like you to do it one more time.”

At this point there was slight dissension in the ranks, like, if we ever meet him, what do we call him? Mr. Gaye? Marv? Marvin? We started to laugh about it, which was bad, but we were getting very, very bored. We thought one of the takes a few hours early on was pretty good, but I think he was testing our patience, too. It got to be 5:30. I had a session at six and other guys had things. I put my guitar down, boldly knocked on the control room door, which was out of bounds to us. That was unusual because were so used to going in, listening to it, and being a part of the production. I knocked on the door, and one of the guys opened it—he was really tall and mean looking—I said, “Can I speak to Marvin Gaye please?” He said no. I said, “Sorry, but we’ve all got other sessions to go to.” He said, “Can you do another half hour?” I said, “I’ll call up and see.” I called and said that we were working with Marvin Gaye—which couldn’t fail to impress the other side—and they said, “Of course.”

Six o’clock came and they said, “Let’s do another one.” We all looked at each other, we knew this was going to end badly. I knocked on the door, and I said, “We have to go. We’re really late now and they’ve already given us an extra hour.” Suddenly Marvin appears. He says, “What’s the matter with you guys?” I noticed that there are people behind him, and right behind me is my lifelong friend, Mo Foster, the bass player. Marvin says, “I am going to make five phone calls to L.A. to make sure you never work in America again.” And Mo says, “Why not six phone calls?”

That was the end of the session, and I never worked with Marvin again. But I did work in L.A. again [laughs].

I read that your favorite session was Tina Turner’s “Let’s Stay Together.” What was great about that?

That was like a day in the life. That whole day was like what sessions were like. How it was diverse in styles and how good it was. I started off that day at 7:30 in the morning and did a jingle until 8:30. Then I went to AIR at 9:30 or 10 to do a live session with the singer, Andy Williams. He used to do everything live. It was with a full orchestra and lovely arrangements. The first song was “Days of Wine and Roses.” The leader counted it in and I played—I had a semi-acoustic, which was a little unusual for me, because usually I’d play Strat—I played about three or four chords, the first bar, and I noticed that I was the only one playing. I stopped, thinking I made a mistake, but he said, “No, carry on.” The first 16 bars were just solo guitar, and it was all these chords that were a fist full of fingers, every extension possible known to man. I did it, and there were two or three songs like that. Andy would say, “I think I’d like to do that again, because he was a perfectionist and it had to be live. He wouldn’t overdub his voice. By the time five o’clock came it was quite a thing, and I learned chords I never knew about. I finished that, had something to eat, went to Ronnie Scott’s to play with the Gil Evans Orchestra. We were there for a week. By that time, I was playing with Gil and we were doing bits of a tour. Our first set was at 10 and we didn’t finish until three o’clock in the morning. I left there and walked with my wife—she wasn’t my wife yet, Sally—she came and met me, heard Gil, and we went to CBS studios down the road, and that was “Let’s Stay Together” with Tina Turner.

We walked in and there’s Tina. We did the track. The track sounded great. I was working with Heaven 17 at the time, the pop band. The producer was Greg Walsh, a great producer who I’ve known for years. We did our thing, and she got up and sang it in one take. You know how great the beginning of that is? That was one take. They said, “Do one more just in case.” She said, “Ok”—she’s a really nice person. She was great. She was talking to my wife, and she got up and did another. They were both fantastic takes. You couldn’t really choose between them. I think it was about five in the morning when we left there. I couldn’t sleep, really, I was so high on that. Someone said to me, music is a bit of a young man’s game, and to a degree that’s right, but you still get so high on the music, and that transcends age.

At the same time you were doing all those sessions, you also had a parallel career happening in jazz.

It was like with playing with Gil, that was part of the parallel. They coincided on that day. Even when I played with John Barry, there was a little jazz scene going. There was Ronnie Scott’s old place, before China Town came to central London, it was there. It was a dump, but it was nice. It was a jazz club [laughs]. I would play there with an organ trio, but at the same time, I’d be playing free jazz things at another club. Free jazz was really interesting to me as it was coming up. I was listening to Archie Shepp and those guys—and obviously John Coltrane—it was a strange thing, because we were doing that and then doing sessions. But the thing is, to me, it’s all music. It’s groove and it’s free. Obviously, the free jazz thing is a lot more group creativity and it’s far more dynamic to actually get that going. Less clues in a way.

The English jazz scene had great players at that time, people like Dave Holland and John McLaughlin.

I had a little trio with Dave for a while, we’d broadcast stuff. He left. CBS wanted to put out something called CBS Realm Jazz. David Howells, he was an A&R guy, he was a jazz fan and he persuaded CBS England to make albums. I made three albums there with them. A lot of people got to know me through that and they got really good reviews. The first album we played songs like “Footprints” and a few original compositions, and then it got more and more far out. By the third album, I found myself more as it were.

Is that Secret Asylum?

Yeah, that’s with the tenor player, Gary Windo, and those guys [trumpeter Harry Beckett, bassist Darryl Runswick, and drummer Alan Rushton]. Live at the I.C.A. was also pretty out there. But I was also doing other people’s jazz things like with Gil Evans. It was more funky.

What was Jazz In Britain?

That was a BBC radio broadcast. We used to do that, which was hilarious because it was all live. There was a guy there called Humphrey Lyttelton. He was a trumpet player, and more than that, a great raconteur. He was really funny. He was aware of the fact that the first band, while he was announcing, would have to creep off with all their gear, and the next band would have to move their stuff forward and be ready to play. That was ok if you were an acoustic band, but if you’re electric and couldn’t play a note to see if your amp was working, that could be difficult. I had nightmares about that, but it was great. I still have the tapes.

There’s a guy now who has the label, Jazz In Britain, and he’s releasing old tapes. I kept everything, not so much the multitrack work, but the old stereo tapes. At the end of each broadcast, there was this thing called the Artist Listening Copy. You’d ask the engineer for one. The music had already been broadcast, so there’s nothing you can do. It was one of those things the BBC had.

Was it a tape of the live broadcast?

Yeah, that was it. No second chances. It’s a fantastic way to play. It’s a different art from the art of preconception when you’re in the studio. That’s still an art form, too, like dropping in and playing eight bars is still an art form, because you still have to make it sound—as my friend Mo says, “contrived perfection”—you have to make it sound like it is all happening anyway. You have to be in the same moment as you were before you dropped in.

How did you hook up with Gil Evans?

There's a trombone player called Malcolm Griffiths and he was playing in the sextet we had. Gil had phoned ahead, or Miles, Gil’s son had phoned ahead. He asked if he could recommend a guitar player, and he mentioned Sonny Sharrock and people like that.

Gil was looking for that?

He was looking for that kind of thing. Malcolm said, “Try Ray,” and got me the gig with Gil. The first rehearsal with Gil, we were in this rehearsal studio in Shepherd’s Bush, and everyone turned up. Gil walks in. He was such a lovely guy and beautiful soul. He is like my spiritual father really, he taught me so much, and just attitude, he was the zen master of jazz really. He came in, and he had a piece of manuscript paper that he had written one note on each stave, just one note. He carefully teared it up, and gave one line to each person, and said, “This is your note. If you don’t like it, you can change it [laughs].” That was, “Welcome to Gil.” Afterwards, obviously, we played his tunes, and it was all the great tunes. We got him to do the Montreux Jazz Festival, and the band was Simon Phillips and Mo Foster and myself. RMS Live at the Montreux Jazz Festival 1983, and the first half was Gil. We played all the stuff like “Gone,” amazing. It was a fantastic moment, a lifetime kind of experience.

When did you start scoring for film and TV?

I’ve done a couple of films, but nothing amazing or big time. My first attempt, I’ll whisper this, I was in a musical called Hair.

You were in that?

When it came to London. A guy called Galt MacDermot wrote it, and that was as about as real as you get. I don’t know if most people remember a day from that because they were so stoned all the time. It was absolutely crazy. We’d sit on the side of the stage, on this make-believe band wagon, and play all the tunes. They wanted to do a new tune and they didn’t have any brass parts, so they asked, “Can anyone write a brass part?” I said, “I’ll have a go.” I wrote a brass part, but arranging, as arrangers will tell you, is like writing a tune. They played that and liked it, and it started from there.

My introduction to TV was a great friend of mine, George Fenton, a composer, lovely guy, and he taught me a lot about writing for picture. I didn’t know that much about it, except that I loved film scores. We started with a couple of things that were very popular here called Shoestring and Bergerac. Most of the stuff I did were detective things, except recently, which is called One Note At A Time, which is about the flood in New Orleans. I also did a thing called A Touch of Frost, which is a really big thing here. For British TV, it was big, at least that was when people used to watch TV, before YouTube, cable, and Netflix. It went on for years and years. That was a great time for me. But George, he let me do stuff he couldn’t do. I learned a lot from that, and just carried on and got more work as a writer. I also did things like production music, which is like library music. It’s like ready-to-wear music, for documentaries and things.

Did your arrangement for Hair make it into the movie?

I don’t know. I can’t say. I never saw the movie to be honest, by the time that finished, I think I was losing my hair. It was great. That was real hippie stuff. Everybody was on it and smoking, I don’t know how anyone remembered anything. I claim not to, the band really had to stay straight because there were all these cues going on, and the cast were relying on us to come in. It got dicey at times, you could see they didn’t know where they were, I mean, in the world. Not just in the tune.

In more recent years, you’ve done at least two projects with Henry Kaiser. How’d you meet up?

Really through Steve Feigenbaum at Cuneiform Records. He sent me his albums. I went to Vegas doing something—more of a business thing, to do with publishing and stuff—but that weekend, when I finished, I went to Henry’s place in San Francisco. I took my guitar and we did an album in a day. I wrote some stuff and sent it over as well. It was lovely, a brass section, it sounded great. I got over from Saturday evening, because it is a short flight from Las Vegas, and we went out and had dinner. I was a bit out if it, double jet lagged, and went to bed. I got up in the morning and he took me to the studio, and we played all day. It was fantastic.

Did you mainly do your tunes or improvise?

Mainly improv. The tunes, with that kind of music, are like the lighthouse really. I tend to put a reprise of that somewhere after a solo, then another solo will come in, with that style. It was very interesting because I hadn't played—we’ll call it free jazz—but I hadn’t played that kind of improvised music for quite a while. Suddenly it was like, “This is what you do here. This is great.”

What's your new album?

I did an album before with Steve. I was talking to him and told him that I have this album. I only make one every five years, I am not prolific like Henry is. Henry’s great. He said he’d love to release it. It’s the sort of album I had to make. It sums up a lot of things about how I feel about music. Steve is one of my favorite people. He’s one of the few good men.

Cuneiform really got hit hard by streaming.

The trouble is, like now, no one is doing any gigs because of COVID. But there’s probably enough music that if there weren’t any more musicians around ever, they would just play music forever anyway. People forgot this, but when they say that the industrial revolution started with the printing press, that means that any time you can duplicate, the original after a while isn’t so important. It's scary to think that if no one ever works again, a gig, that there might still be music. But I think people are losing their thing about going out and hearing live music. It gets to a point where you really miss being in front of an audience. Call it ego, but that thing about relating to an audience, you just don’t do that without doing gigs.