J-Zone Talks Drums, Life-After-Rap, And The Pitfalls Of Trying To Do Everything

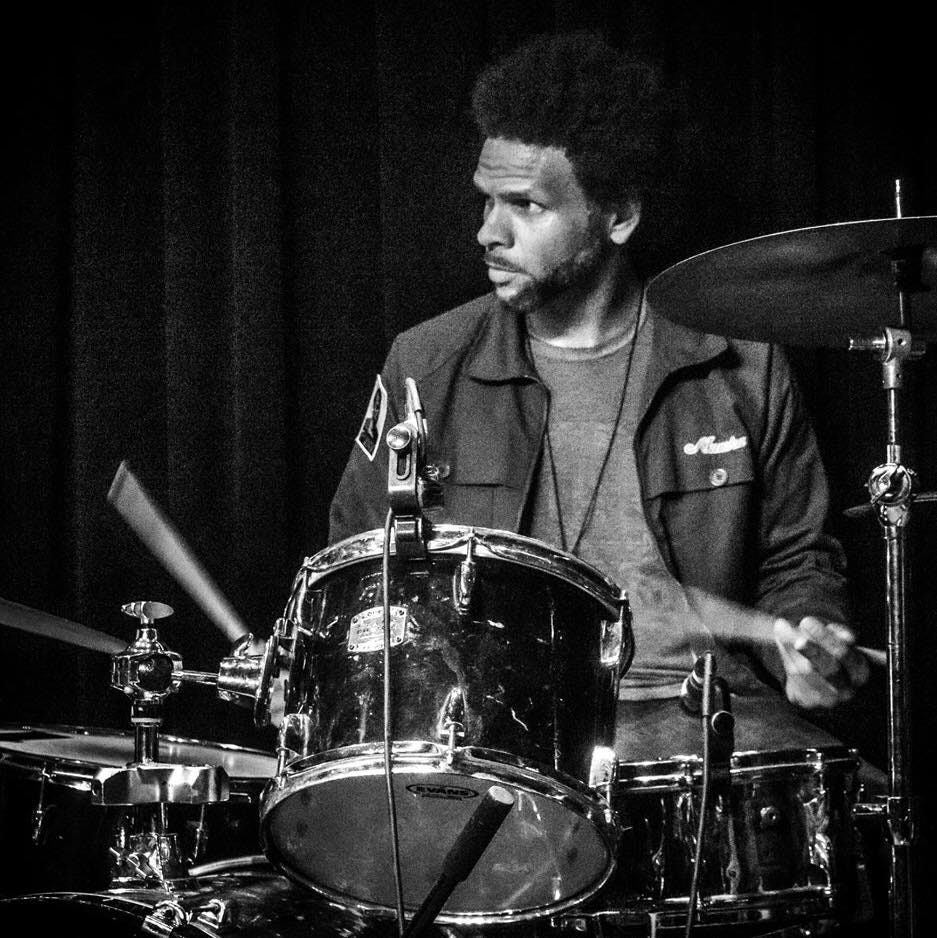

Jay Mumford, better known by his moniker, J-Zone, is a work in progress. He’s worn many hats throughout his career—from rapper, to producer and beat-maker, to DJ, to drummer—and each role, despite the occasional setback, has been creative and fruitful. But his biggest shift came in 2011, when he left rap, wrote his hip hop memoir, Root for the Villain: Rap, Bullshit and a Celebration of Failure, and started over on drums. These days, he is the drummer in a few different bands, although his main squeeze is the Du-Rites, his duo with Tom Tom Club guitarist Pablo Martin.

Mumford is also an entrepreneurial force of nature. He launched, “Give The Drummer Some,” an incredible interview series for the now defunct Red Bull Music Academy—the series put a spotlight on unsung greats from the ‘60s and ‘70s, like Harold Brown (War), David Garibaldi (Tower of Power), Steve Ferrone, and many others—and he recently released his fourth collection of sample-ready, Royalty Free Drum Breaks. His head for business was also an important part of his focus as an adjunct professor in the SUNY system.

“The first thing I taught was an independent study for producers and composers,” Mumford says about his stint as a college professor. “I would try to balance actual production and music with actual business, because at that time at the school, there were no music business classes. If I was working on a contract at the time, I brought the contract in. I said, ‘This is what a contract looks like from Universal.’ I brought in my old contracts for distribution that I had with BMG and showed the class. I figured, ‘Everybody comes here and becomes a master musician, and then they get out there and they go get fucked, because they have no idea.’ I learned by making mistakes, so I showed what I learned through the business side through trial-and-error, and maybe I saved those kids some grief.”

Mumford has been there and done that. I spoke with him about his unconventional journey, his 40-something transition to drumming, the problem with being a jack-of-all-trades, the economics of sampling and providing an affordable service to blue collar beat-makers, interviewing your heroes, and the blessings of bombing at South by Southwest.

You live in Queens, is that where you’re from?

Between Queens and Westchester, which is about 20 miles away. I settled permanently in Queens right after I finished college.

Where did you go to college?

I went to Purchase College, which is SUNY Purchase. SUNY Purchase is the “weirdo, art, hippy” school in the SUNY system, but it was very close to where I grew up in Westchester, so it was just a school that was easy to get to. I auditioned for the music program and got in, and it was obviously a natural fit. I graduated in ’99 with a degree in studio production, but it wasn't like going to an engineering school and you’re just a button pusher, you had to learn music theory, too. I was a minor in creative writing and my senior project was my first album. It served as a transition from college into adult life as an artist.

Did they have you splicing tape or other old ways of doing things?

I knew how to splice tape and all that because in high school, I interned at a local studio in New Rochelle. A guy named Vance Wright—he was Slick Rick’s DJ—Slick Rick went to prison for shooting at somebody in the early ‘90s, while he was in jail, Vance opened up a recording studio in New Rochelle. I was a local kid that he took in. I interned for a summer and then I eventually became a paid engineer. My senior year of high school, I was doing sessions every weekend and making $300. When you’re 17, that’s good money. Grand Puba and Greg Nice, a lot of hip hop guys, everybody showed up. Local guys from Westchester and the North Bronx would show up. I had a lot of experience with the older equipment working at Vance’s, but by the time I got to Purchase, it was all about ADAT, which nobody uses any more. We learned how to mic instruments, which came in handy when I became a drummer later on, I knew how to mic and record live instruments. So there was that and working with ADAT, and learning how to mix records. At that time, we had graduated past 2-inch tape and were moving toward the home recording technology that we have now. From when I started until now, I saw it go from entirely analog to entirely digital.

When did you start working with Pro Tools?

A little bit later. They were talking about Pro Tools at Purchase, but nobody really had it yet, it was so new. I graduated and three years later I had my own home studio, I was using D88 tapes and people told me, “Man, you need to get Pro Tools. You’re sitting here and it takes you four hours to do a clean radio edit. With Pro Tools, you just highlight the thing and that’s it.” My friend went into the service and sold me his Pro Tools he had just bought. And man, I still have that computer today. I never upgraded my Pro Tools. I still have that one.

That must have been 15 years ago?

Yeah, I still have 6.2, I never upgraded. People always laugh at it when they see pictures of my studio, but whatever works for you and makes you comfortable. I am not a propeller head. Too much technology for me gets in the way of the actual songwriting, because I start thinking about how am I going to use these tools, instead of just the animal instinct of laying something down. To me, it’s just easier. I embrace the technology, but I only do it to a limit, to where it doesn’t slow down my brain when it comes to writing the music itself.

You’re a drummer now, but was bass your first instrument?

I played a lot of different instruments. I played saxophone for like a month [laughs], but I couldn’t get the embouchure. I played trombone for the school band for three years, but I used to hate that you had practice at 7:30 in the morning. Then, first thing, you’re tired and you take out the mouthpiece and it smells terrible, it was just disgusting. I didn’t like trombone, man. I said, “I am not going to do horns.”

There was a funk band called Slave, they were a late-‘70s, early-‘80s funk band from Ohio. I discovered their music in my mother’s record collection. The bass player for that band was a guy named Mark Adams, and he was like Jaco Pastorius, but funk. He had the dexterity of Jaco, but he played a nasty, growling bass. I fell in love. I got a bass for Christmas out of the Sears catalog and I started playing. I got really good, really fast, because I had all these funk records in my parents collection. I would also buy records with my allowance from the old record shops—my dad would take me—and anything that was funky, I would take it home and play bass to it. I learned entirely by ear. I eventually started playing upright bass in the orchestra, playing classical music. I did that, and I played bass in the jazz band as well. I learned how to read music and I took a couple of lessons, I started playing properly, not just by ear and feel, but I started learning how to read.

But the kind of music I wanted to make was ‘60s and ‘70s-type funk. At this point, late-‘80s early-‘90s, live bands were falling out of favor—not just hip hop, but in R&B music, too—drum machines and synthesizers had replaced everything. People were making albums with just machines and everybody was going towards producing. There were not a lot of people trying to play music, there were, but everybody wanted to play rock or jazz, nobody was trying to be a funk musician. I said, “What are the odds of me finding seven other guys and starting a band in suburban Westchester county? I am going to play classical music in school, and I am going to play funk in my bedroom by myself to an audience of no one.” That was not practical.

At that time, I had gotten into hip hop because all my friends were into hip hop. But I was the only one who didn’t like hip hop all that much. I thought it was cool, but I didn’t care. But then I started paying attention. My friend said, “Turn on Yo! MTV Raps and watch it.” I did and I fell in love with it—LL Cool J, Big Daddy Kane, Ice-T, Stetsasonic, Heavy D, NWA, Public Enemy, all these groups at the time. I watched MTV Raps, listened to hip hop, and started noticing that in their music, the beats, I started hearing the records I used to practice my bass to. I thought, “How are they doing that? That’s the record I played to every day, how is it in that song?” That’s when I discovered sampling. I started buying rap magazines and watching a lot of public access hip hop shows. They would have producers in there with [Em-u] SP-1200 drum machines, showing how it was done. I used to read articles about sampling and all that shit, so I figured that out, and eventually realized that I can do that by myself. I was about 12 or 13 and I knew that kids my age didn’t collect old records. I had an advantage. I was a young kid who had an encyclopedic knowledge of old music. I thought, “I know all the records. If I start making beats now, I am going to be a beast.” I got a cheap sampler, got my stuff together, and eventually saved up money and I got an SP-1200. I started interning at all these recording studios, like Power Play Studios in Queens [in Long Island City]—I already told you I worked with Vance—and as I started interning, that’s where I picked up all the rest of my technical chops. I was very well schooled. Back then there was no internet so you had to look through the phone book and find the studios and show up. “I want to learn this. There’s no pay, but I’ll mop the floors and you let me sit in a watch a session.”

But these days, you’re a drummer.

Drums are my instrument. Throughout my entire career I was known as a jack-of-all-trades. That was my thing, and I prided myself on that. But when I turned 40, I had a DJ residency, and I got fired. I was thinking about how to replace it with another DJ gig, and I had an epiphany. I thought, “I can do eight or nine things decently, but I’ll never master anything doing that many things.” I took a risk. I stopped doing a lot of things, and put all my time into composing music, playing drums, and writing. You either have to devote yourself to a craft or it’s going to be a rough ride. I wish I figured that out sooner, but I figured it out with enough time to tighten up on the things that I really want to focus on.

Are you hyper-focused on those things now?

Yeah, composition, production—not so much from a hip hop, beat-making standpoint, but putting songs together. I am always going to be a producer, just not in a beat-maker sense. I am a producer more in a composer sense. Songwriting. That’s what’s going to be your annuity. There are tons of musicians who can play their asses off, but they didn’t write the music. Fifty years from now, when the royalty checks are coming out, you may have played on it, but you’re not really going to get anything. You have to write music that’s going to be used, played, and licensed for years to come. I am learning, and now my ASCAP check is starting to pick up. When I was a hip hop artist, I never got ASCAP checks. One day, I am not going to be healthy enough to lug drum kits all over the place—or I might not want to, or I might be tired. If you write a hit song, you can always depend on that check. That’s all musicians have in terms of longterm security.

Is that the intention your behind Royalty Free Drum Breaks?

Well yeah, but a lot of those are money in volume, because people buy them. I sell the 7-inch vinyl and then people buy the digital, so that’s a good constant revenue stream, because people always need drums to sample. But I am not going to sue some guy with a Soundcloud page with 100 followers. Twenty years ago, I’d make beats and sample drums. Eventually, who sampled was established, and then people started getting sued retroactively left-and-right over drum breaks, and a lot of these producers are on Bandcamp selling 100 copies. You press up a CD, sell a few copies, and you still get sued—there’s no money. I’d rather just say, “That's J-Zone playing the drums”—buy a copy of the break record for $25 and we’ll call it even. I really don’t care about getting rich off of some blue collar, low level, independent hip hop. Now, if someone looped up my drums and they made a record for freakin’ Taylor Swift, then obviously, it would be great to get publishing and credit so I can get more work. The whole thing is to build my profile as a drummer, to get more work and to get publishing if the record is a huge hit. But for guys who just make beats and put out independent hip hop releases on small labels, I’d rather just get a credit. What am I going to do, get mad because I’m technically owed $22.16 for this drum break? If you buy the break record, that’s what I’ll get anyway.

Are those selling?

Yeah. They do well. I am sold out of the first three and the fourth one came out on vinyl on December 11. The digital continues to sell when the vinyl goes out of print, and every month there’s a royalty check for sales. It’s cool to see my name appearing on records, and I tell people, I do want credit. If you do liner notes or you put metadata on your release, I do want credit for the drums being from my break records, so somebody else can go buy it.

You started playing drums much later in your career, how did that come about?

I was away from hip hop. I was teaching, and I had just published my book. The week my book came out, I got my first drum set. That was the end of a chapter, and from there, I started focusing on drumming on the side—just my own personal mission to learn an instrument. I kept it pretty quiet for a long time, I just did it as a hobby. After about a year, I was thinking about what was I going to do next with my life, as in, “What’s my longterm plan?” That’s when I started working at night and practicing during the day, doing five hours every day like a high school kid would do. I was in a very unique position. I wasn’t making a lot of money and I was struggling finding a thing, but because of my situation—I was home durning the days taking care of my grandmother. She was elderly at the time, and I was like her home caregiver during the day. She was hard of hearing, so when I would beat up on the drums from 11 to 5, she wouldn’t hear me. I did that every day, and before I knew it, after a year I would start playing for people and they would say, “You’ve only been playing a year?” But if you take any adult and put them on an instrument five hours a day for a year, they’re going to get good fast. But most adults, that’s not their reality, they don’t have that kind of time.

Plus, you were already a musician. You knew music.

I already had an ear. I knew what it was supposed to sound like. I had a great sense of tempo from DJ-ing. I was also a hip hop producer, and everything in the drum machine is tempo-locked. You have that metronome in your head when you’re making a beat. I was used to working with metronomes. I was used to the pocket, groove, things sounding good, dynamics—being a DJ, bass player, and beat-maker all those years, all that experience gave me a giant advantage. The real hurdle was technique. Physical. Coordination. Separating the limbs. Dynamics. Relaxing on your instrument and not getting tense. The physical part was rough, not speeding up—all drummers speed up in the beginning, I still speed up sometimes—it’s just natural. All those little things, but I wasn’t going into drumming with no background. I had plenty of experience, I just had no hands and no feet. I knew what good drumming sounded like, I just had to work hard to get there so I sounded good.

What was your first gig like as a drummer?

My very first gig [laughs], I had two because one of them was like a half-a-gig. The half-a-gig—and you can’t make this shit up—my first time ever playing in front of people, I shared a drum chair with Questlove at Mobile Mondays, which is a DJ night in New York City that I used to DJ at all the time. That night it was Just Blaze’s birthday party. Just said, “I want you and Quest on the drums”—because he knew I played drums. But I played in my basement, I had never played live. I was recording, playing in the basement, and jamming with other musicians, but never in front of a crowd. I was the warm up drummer. When the DJ played a song, I played along to it, but it wasn’t like a show, it was a DJ and drummer playing along to the music. I didn't play that long, but that was my first time playing in front of people, and I was on a bill with Questlove.

Was Questlove supportive? Did he like your playing?

I was off by the time he came on. Two months later, Just Blaze showed him an Instagram clip of me playing and he shared it on his Instagram. A month-and-a-half later—after the half-a-gig with Questlove—I was one third of a hip hop supergroup, although the album never came out. We had a show at South by Southwest where I had to rap and play drums. It’s the only time I’ve performed a rap show between 2007 and now. I played drums throughout the set, and we were horrible [laughs]. Somebody threw a wet tissue at me. I tripped over a cord running back to get back on the drum set. Our time was off. We were totally unrehearsed. It was one of the most embarrassing moments of my career, but it was also one of the most important. I had a ski mask on when I performed—we all had ski masks, so nobody except people back stage knew who we were—and I am going to leave it at that. But it was one of the most important things that ever happened to me, because I had come back to music in 2013. I was playing drums and rapping and producing and DJ-ing and writing—from 2013 to 2016—I was doing all those things, anything to make a buck. Behind the drum set, I didn’t sound good, but I knew in my heart that this was what I want to do. Whereas every time I was on the microphone rapping, I wanted to blow my brains out. I just said, “I am done with rapping, entirely. I am not going to make any more records. I am not going to do it here and there. I have no interest for the shit anymore.” I hadn’t done it nine years prior to that, it was just a one time fluke. But you know when you make a decision, and you know that it’s the right decision, and then you think, “Try it again, it’ll be different this time,” and the minute you get up there you say, “Nah, I had it right all along.” The minute I got on the mic, I said, “I should have just stayed my ass retired.” After that show, it was awful, but it was a real eye-opener. Drumming is where my heart is and where I want to be, but now I saw how much I had to put in.

I first heard about you from your “Give the Drummer Some” columns for Red Bull Music Academy. How did that come about?

When I first started playing drums, that was part of my education. All the drumming that inspired me was a very specific style of drumming—funk, break beats, the shit that was sampled for hip hop. I said, “This is twofold. I will reach out to these guys for the selfish part of me, my research, my music nerd shit, and answering questions that I’ve always wanted answered. But from the other side, it’s a chance to show the world what these guys did.” Not a lot of them got the credit or money they deserved. Nobody’s done interviews with these people in a searchable medium, where you can get easy access. Some of those guys I interviewed had never been interviewed before. One guy, I tracked him down through the Yellow Pages, and he’s never done any press whatsoever.

Who was that?

Dwight Burns, he played on Archie Bell and the Drells, “Tighten Up.” Everybody knows, “Tighten Up,” it’s one of the most popular R&B songs of all times, but nobody knows his name. I hunted him down. We remained friends and we still talk. He’s in his 70s. I made a connection to these people I had listened to for years. They were grateful to have a place to tell their stories, and I was grateful to soak up all that information. Even when the tape stopped rolling, they would give me pointers and advice about hand technique and different kinds of drums. When I auditioned for the soul band I play with, Ben Pirani and the Means of Production, I interviewed Steve Ferrone the same day. He was the drummer for Average White Band and Tom Petty, and I think he played with Eric Clapton. He’s known for having an insane pocket and great time. He’s not flashy, but everybody loves him because he’s a groove machine. I said, “I have this audition tonight. I am nervous, I don’t have a lot of experience playing live.” He said, “Don’t be fancy, just play the song. Play the groove and don’t show off. Don’t try to start doing fills.” I went in there, did it, and got the gig. After that, Ben, the leader of the band, said, “You know, you can do some fills.” “OK, Steve told me don’t do no fills.” It helped me in my own development as a drummer to speak with these guys who’d been there before. To be doing that in your late-30s and early-40s is wild.